By Justin Zackal

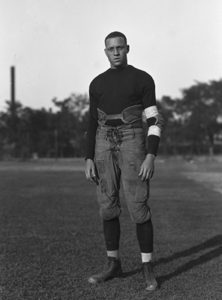

Photo of Dr. Charles “Pruner” West courtesy of W&J College.

The late Dr. Charles “Pruner” West is often recognized for his role in a football game that ended with a score of 0-0. But he was most grateful for a “game” that was recorded as a 1-0 win

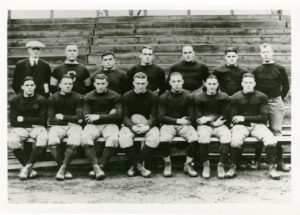

West, who will be honored prior to the fourth quarter of Monday’s Rose Bowl for his induction in the game’s Hall of Fame, was the first African-American quarterback to play in college football’s oldest bowl game. West lined up under center for Washington & Jefferson in its scoreless draw against the University of California, Jan. 1, 1922, in Pasadena, California. (Watch video of the 1922 Rose Bowl courtesy of the U. Grant Miller Library below this article).

A halfback who had to play quarterback because of injuries, West and his teammates played both offense and defense (the smallest school ever to play in the game could only afford to travel 11 players). The Presidents were part of many stands against Cal, limiting the Golden Bears to 49 yards, all rushing yards, but there was a more compelling stand that W&J took two seasons later.

W&J, coached by John Heisman (yes, that Heisman), hosted Washington & Lee in 1923 but the Generals refused to play against teams with African-American players. They asked W&J to sit West for the game, but W&J Athletic Director Bob “Mother” Murphy, a man who remortgaged his house to pay for his trip to California for the Rose Bowl two years earlier, left it up to West whether his team should accept the opponent’s demands. West said that he can’t stop them from playing, but he’d never play for W&J again if his team chose to play.

The Presidents didn’t play and the Generals forfeited the game, resulting in a 1-0 W&J win, and Murphy paid W&L a portion of its share of expected gate receipts.

“My father was always just grateful, so grateful, for the stand Mr. Murphy took against Washington & Lee,” Linda West Nickens, West’s daughter, told W&J Magazine.

Nickens and West’s grandson, Michael Nickens, accepted a trophy to commemorate West’s upcoming forthcoming honor at a W&J game in November. Tournament of Roses executives Brad Ratliff and Leo Cablayan spoke at the ceremony, along with W&J president John C. Knapp.

“Charlie West represented our athletic program exceedingly well,” Knapp said at the ceremony. “He was exemplary of this college’s longstanding commitment to being an inclusive place where regardless of one’s background or race or difference, there’s an opportunity to be fully included in this community and be part of the success of what makes W&J, W&J.”

The Rose Bowl’s theme this year is “Making a Difference,” which is befitting for West, who went on to maintain a general medical practice for 50 years in Alexandria, Virginia, to be inducted in this year’s class that also includes former Texas head coach Mack Brown, UCLA quarterback Cade McNown and Michigan’s Heisman Trophy winner Charles Woodson.

“Washington & Jefferson gave Charles West that chance to make a difference,” Ratliff said at the ceremony. “(With this recognition, we) can tell others about the value of men like Dr. West and the lessons he learned on the field and the value and the commitment he had to make a difference in the lives of countless others. The school accepted Charles West and because of the actions of a forward-thinking college, thousands of people benefitted from the success of an African-American man.”

The 1922 W&J Football Team courtesy of W&J College.

Linda West Nickens also shared stories about her father, including how his W&J teammates sat with him in the “colored only” train car during their cross-country trip to the 1922 Rose Bowl; and how he qualified for the 1924 Olympics in the pentathlon and made the trip to Paris, but he had a hamstring injury that put his participation into question, and despite quickly recovering, French officials refused to let him re-register.

“Charlie West’s journey was not easy, not just for this trip to the Rose Bowl, but his journey into manhood and all through life,” his daughter said at W&J’s ceremony. “One of the great lessons he taught me, mostly by example, was how to handle the inevitable disappointments that we all face with grace and dignity.”

West grew up on a farm in Washington County and his father opened a drug store, which led to West’s nickname, “Pruner,” a mispronunciation of “Peruna” cough syrup sold there. After earning his degree from W&J in 1924, West had an offer to play professional football with the Akron Pros, but he chose to attend Howard University Medical School in Washington, D.C.

West received the W&J Distinguished Alumni Service Award in 1978 and he was inducted into the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame in 1979. He died later that year on Nov. 20, 1979.

“Charlie didn’t set out to break down racial barriers,” his daughter added. “He just wanted to play football and run track, both of which he’d done from childhood. But he did, in fact, become a pioneer. Thinking of his own role in integrating athletics in American schools, he said, I’m very proud to have played a part in shaping the destiny of the black athlete in this country.”